The Artist at Work

8 October 2022

From the diary of Miss Lillian Stirling, June 1912

On the occasion of Cecilia’s nineteenth birthday, Mr. Woodburn proposed an outing to the conservatory, and because Cecilia could not produce any plausible and also polite excuse not to, we went. This was on the Tuesday two weeks past. Despite many attempts since, I have not been able to set down a record of that day. I still remember all, however, with the clarity and tenacity of true horror and penance.

I was eager then, as I was with any fresh opportunity to improve Cecilia’s opinion of that gentleman. I puzzled over her aversion to him. He was only some five years older than she, with a pleasant appearance as well as manner. He had also financial means beyond ours, which compelled Cecilia’s attention as a matter of our own necessity. Of course, I still am possessed of a great guilt about our constricted circumstances, but I must admit that, had I been my younger sister, I would have delighted in such a necessity as he. But I am not Cecilia, more’s the pity. Instead, I trot along behind her as chaperone and sometimes confused companion.

On the day we went to the conservatory, Cecilia’s reluctance to participate in the event was palatable until, upon his arrival, Mr. Woodburn announced he intended for us not to travel as usual in his buggy but to board the elevated train that headed east to the city. This inspired in Cecilia if not a reversal of emotions at least a decided brightening of them. She is fond of the elevated train and we have few reasons to use it. I find it rather too fast and too far removed from the solid ground to enjoy, but that was no matter. I was content to watch her grey eyes shine as she gazed down at the roads and parks underneath us.

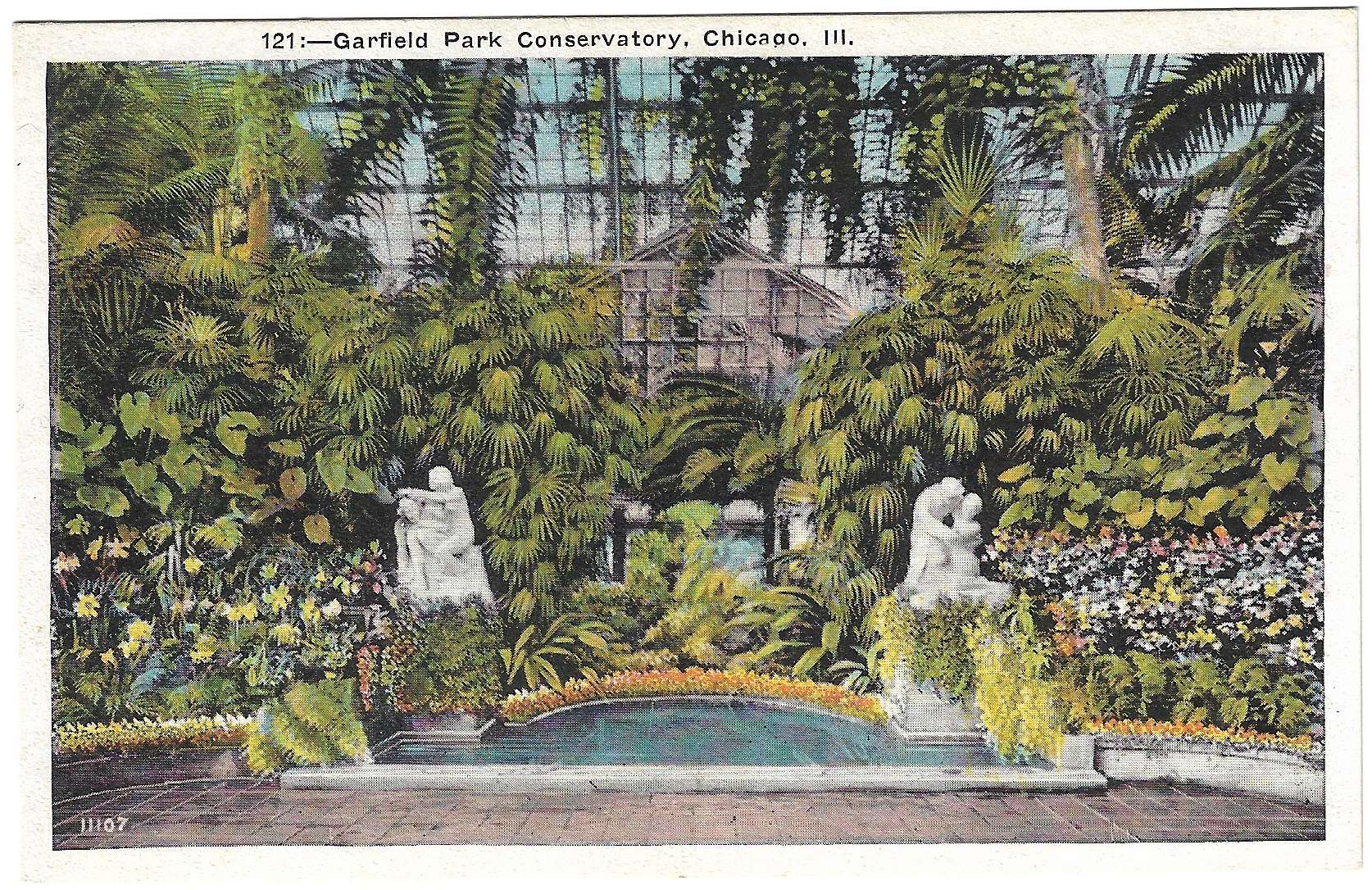

We descended at the station in Garfield Park and walked to the conservatory. Sunlight glinted off of its sloping glass dome, shining like a beacon. I shaded my eyes until we stepped inside and, once enveloped in its green and warmth, I breathed a sigh. Unlike the train, I am quite fond of the conservatory. While Cecilia had adopted the aloofness she always bore like a shield in Mr. Woodburn’s company, I knew that behind it she was also excited. We could go there only rarely, but the conservatory is a place of loveliness and peace, where we might stroll, relax and lose ourselves in a world with far more ease and grace than the one outside. Sometimes I could even forget those things that dogged me in daily life. I recognized that perhaps I did not deserve to forget those things, but the past two years following our father’s death had been so dim, confused, and disappointing that I reached for any light I could find. I reveled to be in the conservatory. Even with Mr. Woodburn in attendance, Cecilia could hardly contain her enthusiasm. She floated along, anchored only by one hand captured in the crook of Mr. Woodburn’s elbow, a delicately leashed butterfly flitting through the flowers, trees, and plants.

As we rounded a corner in the Palm Room, we came upon a woman painting on an easel. On her canvas sprouted the same scene of palm trees and flowers before her, stroked with skill and grace. We collectively murmured our appreciations, to which she did not respond, and moved on into the Fern Room, where Cecilia broke free to rush ahead, skipping over the stones laid as a pathway. Courteously, Mr. Woodburn turned to help me along the uneven surface.

“It seems our explorer has no need of my guidance,” he said to me ruefully but with good humor. Mr. Woodburn is a man of twenty odd years, slender with a long face, deep brown eyes, and a wave of sandy hair, and, until a significant point later that day, I had never seen him in anything but good humor. I am not certain even now how we first made his acquaintance, but the misgivings I would normally have about such murky origins were wholly conquered by his pleasant nature and the consistently thoughtful, respectful attention he showed to my sister. Cecilia is a pretty, spirited girl, and because our family has little else to offer a man of his apparent wealth and standing, I felt convinced he could desire nothing but her for her own sake. He had been carefully courting her for some months now and I fully expected a proposal inside of the summer.

I took the offered arm that Cecilia had abandoned. As always, I felt a mild irritation with her for not properly appreciating Mr. Woodburn’s kindnesses, but it was subdued by my confidence in his intentions, as well as my own smothered delight in being on the receiving end of such kindnesses. I would not confess that any place other than this personal record. It is, however, the truth, and I must make a full confession to my part in this incident, as the enabler of our association with him.

We began to circle the Fern Room, filled with masses of prehistoric greens and centered around a serene pool. At the back of the enclosure, a small waterfall tumbled over rocks. It broke through the pathway in shallow streams on its way to the central pool. Cecilia bounded from touchstone to touchstone across the streams. I thought to call and warn her about slipping on the wet rocks, but by the time I opened my mouth, she was already crossed. Mr. Woodburn took a firm hold of my arm with both of his hands to bring me across as well.

“Miss Stirling,” he said to me as I kept the edge of my skirts up from the water, “I suppose that because neither your father nor mother are available, I must apply to you to discuss Miss Cecilia. Perhaps I could call on you later this week.”

I flushed with his implication as if I were the prospective bride myself. “That is kind of you, Mr. Woodburn. I should be happy to help, but I believe in this case you should settle the details with Cecilia directly. That suits her character, and I do not imagine I could have any objections.”

He did not respond to me and, now on the other side of the stream, I glanced up at him. His eyes were on Cecilia, swaying down the path ahead of us, one small white hand caressing the reaching ferns as she went. “I am certain that Cecilia will have no objections either, “ I reassured him.

Mr. Woodburn blinked and returned to the present moment by my side. He smiled at me and drew my arm more comfortably through his. “I am certain of that as well.”

We walked for another moment. Presently, he said, “I should like to depart the city by fall. Of course, I inform you of all of our travel arrangements so you know where to direct your letters.”

For the first time in our acquaintance with Mr. Woodburn, my anticipation of Cecilia’s future with him faltered. I felt an odd pinch around my heart. “Oh, have you planned a wedding trip already?”

Mr. Woodburn strolled along with a strong, wide stride, drawing me along behind him. “I have long intended to spend some time abroad in the coming years. Cecilia will enjoy that, will she not?”

Indeed, travel would suit Cecilia’s wanderlust quite well, but my own good feelings were crumbling. I had not thought he would take her away from me, not for years. I must admit that I also hoped if they were to take any significant trip, that I would be invited along, as I had been during their courtship. Evidently, Mr. Woodburn’s thoughts were different. He seemed to want her to himself. As her husband, that was an arrangement to which he would have every right.

How could I avoid contemplating how awry my original plan had gone? I had thought to secure independence for Cecilia and myself in those murky days before our father’s death. But I failed to ascertain the whole truth of our family’s financial situation before I acted, and so we inherited little more than debt to pay. Then I had believed I could not hate Father more in death than I did in life, but I had been mistaken. Now, I had latched on to Mr. Woodburn as our next solution only to discover that too seemed a more challenging bargain than I had anticipated. No matter what the intention, the consequences come from actions taken wrongly.

We walked along, even though I had fallen into a troubled silence. The path led us back into the Palm Room and soon back around to the woman painting at her easel. Here we caught up with Cecilia, who had paused behind her to watch the swift, sure movements of her brush.

The artist seemed to me a genteel sort, but she did not cease her painting to greet us in this second moment of interaction either. Her graying hair was bound sensibly at her neck and she wore a smock to cover her dark dress. A pair of wired spectacles perched on the tip of her nose and she tilted her chin up to look through them at the scene in front of her. Her paintbrush hardly rested as she did so, as if her body already knew what to paint without the aid of her sight.

The painting she created was a fine one. She was clearly an artist of talent and expertise. My attempts at drawing or watercolors had always proved dissatisfactory, and while Cecilia had a knack for line and color, she had not the experienced hand of the woman who then worked before us. I leaned forward slightly to examine the painting, and it was only then that I noticed that between the image on the canvas and the scene laid in front of us, there was a large, dark discrepancy.

On the artist’s canvas, standing among the painted palm tree trunks and flowering bushes, there was a woman dressed in black. She stood near the far wall of the conservatory, half in palm leaf shadow. Her black gown came up to her chin and fell to her feet. In her hands she twisted a silken scarf of green and gold. A dark veil filmed her face, but her face shone through, wide and pale white. Behind the veil, her eyes were round and dark.

I looked past the canvas at the spot the painting depicted and saw it all just the same, except the woman. It would have been exceedingly strange if there had been a woman skulking in the shadows of the Palm Room at the Garfield Park Conservatory. But even stranger was the apparent fact this artist had chosen to include in her work such a vision that had no match in reality. It was so odd I felt compelled to inquire her reason. Before I could address her, however, I became aware that Mr. Woodburn’s arm had locked stiffly around mine with the tension of a steel trap.

Only then did I realize how swiftly and fully his demeanor had transformed. Gone was any trace of his former good humor. The healthy flush had drained from his countenance and there was a wild sort of strain around his eyes. He stood still and stared at the painting on the artist’s easel with something like terror.

“Mr. Woodburn, are you quite well?” Rather than reply to me, he violently shook off my arm and strode to the artist. Cecilia had turned and also noticed his evident distress. She looked at him curiously as he reached past her to stab a finger at the canvas.

“What is the meaning of this?” he demanded of the woman at the easel. She, unruffled, gazed back at him with nothing but one raised eyebrow.

I rushed forward and pulled Cecilia away from both the artist and Mr. Woodburn. I did not know what was happening but I thought she should be away from it. We watched from a few feet away as Mr. Woodburn towered over the artist. She bent backward slightly like a birch but did not break even as he began to shout. “Who sent you to play such a vile prank? Woman, you will answer me!”

The noise and commotion began to attract more attention and I sensed more conservatory patrons gathering behind me and Cecilia. Opposite us, a gentleman had come upon the scene from the other side and, perceiving the situation, came to the defense of the artist—although it is true the artist, beyond the fact she was a woman much smaller than Mr. Woodburn, did not seem to require defense. She had said nothing, a brick wall against her accuser’s noise and encroachment.

“I demand to know who put you up to this!” Mr. Woodburn continued shouting even as the other gentleman took a hold of his arm and tried to lead him away. “You will tell me who told you to do this!”

The men scuffled and at once Mr. Woodburn swung his arm around and connected his fist with the other man’s chin. The man stumbled backward and Mr. Woodburn fled past him, down the path towards the front of the conservatory, disappearing soon from our view.

The woman at the easel calmly set down her brush and lifted the canvas from its perch. She brought it to Cecilia. I was too shocked at the time to prevent Cecilia from accepting it. Cecilia studied the painting and traced the edge of the veiled woman’s face as the artist packed up her materials and prepared to leave.

Presently, we left as well. What else were we to do? Mr. Woodburn had vanished quite completely by that time. I must note that now, two weeks later, we have not seen nor heard from him at all. My quiet inquiries have yielded no rewards. All I have learned is that Mr. Woodburn has reportedly vacated the city entirely.

In truth, I have learned one other small piece of intelligence, but it is so outlandish I can scarcely take it seriously. Mrs. Lovelace wrote to report that she had heard Mr. Woodburn had been married once before to a girl who died not long after her marriage. Mrs. Lovelace gave no more detail than that; however, I took her meaning. Our Mr. Woodburn had secrets not revealed to us. We are fortunate that Cecilia’s fate had not been sealed before those secrets came to light.

For her part, Cecilia has been in high spirits ever since Mr. Woodburn’s sudden and perplexing departure. I daresay she feels vindicated in her earlier distaste for the man, as I feel chastened for my immediate approval of him. But I am glad she is not taken from me, and I have learned many lessons for the future.

I have no urge to revisit the conservatory anytime soon. But I think often about the woman we encountered there, the artist who painted something that was not there but seemed to be real for all that. Perhaps it was all as Mr. Woodburn accused: A vicious prank enacted by someone who knew a secret about him we did not. The entire situation has been so disorienting that I cannot dismiss the prospect of some instinct of the artist beyond our human reason or understanding.

It is about the artist I still wonder. I do not believe I had ever seen her before and I shudder to think of seeing her again. I imagine rounding the curve of a path and finding her small, smocked form in front of her easel, her brush flitting and dipping through the paint with distressing certainty, and on her canvas a picture taking shape of something I do not want to see.